The Greek value of filoxenia

By Dr. Katherine Kelaidis, Director of Research and Content at the National Hellenic Museum

My dining room table belonged to my grandmother. She inherited it from her grandmother, who had it shipped in a steamer from Chania, Crete to New York City, before being placed on a train and taken all the way to the deserts of southern Utah. It was the only thing Yiayia Saradakis brought with her from the sprawling Venetian-style townhouse she left behind for America following the failed Cretan Uprising of 1889.

Decades later, as Hitler’s war planes buzzed above Cretan skies, dropping the bombs that would destroy that abandoned townhouse, sitting at the table in the vast central room of a boarding house in Price, Utah, waiting for news from “home,” Yiayia Saradakis would tell her granddaughter, my grandmother, that she had brought the table with her, despite the obvious difficulties, because she knew that if she had a table where people could gather, eat, fight, and laugh then everything would be okay. Everything would work out somehow.

Some of my earliest memories are of holidays and Sunday night dinners gathered around this table, filled as it so often has been with people and food, laughter and shouting. This table, made from increasingly rare Lebanese cedar, symbolizes to me the very best that I have received from my Greek heritage: family, food, laughter, and an uncompromising commitment to bring people together no matter what is going on outside the walls of the house, outside the protective bubble of a filled table.

I have been thinking about this table, my table, a great deal as we move into the holiday season. Not just because I am once again preparing to gather friends and family around it to eat a multicultural menu that is simultaneously American, Greek, Mexican, French, and whatever might catch our fancy, but because as the world seems increasingly to have gone mad, I am thinking more and more about the power of a filled table. I have come to realize that Yiayia Saradakis was right: As long as there is a table at which we all can eat, we will be okay. Everything will work out somehow.

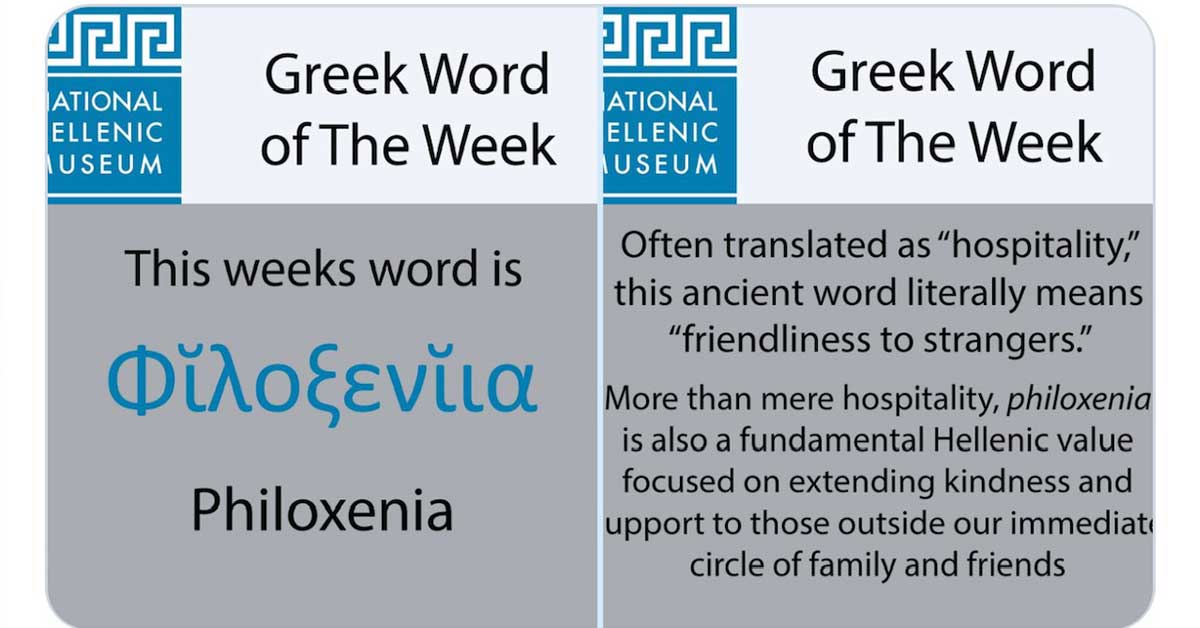

This idea is at the heart of the fundamental Greek value of filoxenia, which while often translated into English as hospitality, might be better understood as the obligation to share our lives and livelihoods with others, to offer welcome to all without questions or hesitation. From Homer to the dinner tables of Greeks around the world today, filoxenia has formed a fundamental part of how Greeks understand themselves and are seen by others. We are a people who welcome others at our table. Filoxenia has consequently provided the folk explanation as to why Greece’s tourism industry leads the world and why the Greek diaspora dominates the restaurant industries of so many countries.

And in a deeply divided world, the virtue of filoxenia, whether at our own dinner tables or in the public square, is yet another gift the Greeks can offer the world. Because as long as we can sit together and eat, we can keep talking. And certainly if we keep talking, we will inevitably argue. But here is the important thing I learned at Yiayia’s dining room table: If we stay at the table, through the argument, through the shouting, through the misunderstandings, eventually the argument turns to laughter. Because we came to the table in the first place as a family to eat, not as enemies to fight. At the table, we eventually all come together.

To learn more about how Greek food and philoxenia helped create the American diner, join NHM Discussions online on December 7th at 5 PM. You can register here.

If you would like to know more about how the Hellenic legacy lives today in Chicago and beyond, please visit us at nationalhellenicmuseum.org to learn more about our work and support our effort to promote inquiry and share the Hellenic legacy for generations to com